A FLYING FORTRESS TAKES OFF... TO WARSAW!

A report by cpt. M. Kowalski (pilot) made from British airstrips before the American operation to the fighting Polish capital.

When the Polish Air Force Command was notified that one of the American bombing divisions was ordered to make a larger scale drop for the fighting Home Army in Warsaw, the commander of the Polish Air Force, Gen. Irzycki, together with the head of the Air Force headquarters, went to the headquarters of the said division.

In the headquarter of the American general

Somewhere in England, in a country house turned into quarters for the American, the general in command of the bombing division, received the Polish guests. Slender, tall, with a calm and sincere face, the American general did not look more than 25 years old. He led us to the operation center, where large maps hung.

On one of the walls hung a two-storey high map of Europe - from the British Isles to central Russia. On it were different coloured strings, corresponding to the operation routes planned for the next day. One of these strings, a red one, extended to the city of Warsaw – that was “our” operation.

The general began to explain to us the plan of the intended operation. Additional protection was to be provided for almost the entire passage by fighter pilots. The flights were to be carried out during daylight hours.

At one point, some Polish army and air force officers entered the operations center. Among them was the commander of the Polish air force unit, which for the last months had been carrying out night flights to Warsaw, providing the struggling capital with what help was possible up till then. All those who entered the center had been busy for a few days delivering the containers, or metal boxes, into which the items which were to aid Warsaw’s fighting were packed. In addition, our officers supported the American’s with all possible information, on the basis of which the details of the expedition were prepared, together with the necessary information for the flight crews.

The Poles could not participate in the actual operation

We asked the American Chief of Operations if there was any possibility for Polish officers to accompany the American expedition. We pointed out that it was an expedition of historical significance and that we, the Polish side, would like to have our own documentation and observations from this undertaking. In addition, we emphasized that Polish air force officers present in American planes would be able to give additional information, when over Warsaw, which might be needed to ensure the total success of the drops. In response we heard: “It is necessary to obtain permission from all our senior authorities – we ourselves would gladly take you with us.” We understood this answer to be a courteous refusal.

At the briefing

Before midnight, we parted for our designated quarters. Not for long, however, because we were told that at three o'clock in the morning we would be going to a nearby airport by car, where the crews would be briefed.

Outside, a thick fog had spread over the ground. Through it the crescent of the moon, in the final phase, was hardly visible. The car struggled forward, and we were seized with fear for the fate of the operation.

In a large tin barrack of the “barrels of laughs” type, a few hundred crewmen with the commander of the entire operation were waiting for our arrival. The briefing began with an introduction for the American airmen of the main points. The information captain who was entrusted with this task said the following:

“Today's expedition is a direct result of our President's conference with Prime Minister Churchill in Quebec. They came to the joint conclusion about the need to increase assistance to Warsaw. Our bomber division has already participated in this kind of mission on three occasions, by dropping weapons and ammunition for the French Maquis. You remember how generously you were rewarded for the results of the help you gave to the French Underground Army. Today Warsaw, which has been fighting with the Germans for many weeks, is suffering from a lack of weapons and ammunition, is awaiting similar help from you. You will meet Soviet fighter planes over Warsaw, and after your flight (to Warsaw) you will land in Russia.”

The captain went on to provide information on how far his own fighters planes would offer cover. The drops were to be made in two places, and for this purpose the planes were divided into appropriate groups for the regions assigned. Having cast the map of Warsaw onto the screen, the speaker explained, as if he knew the capital (Warsaw) perfectly, all the details depicting the area dominated by the Polish Home Army. He explained how to recognize the districts on which the drops were to be made.

He next gave the meteorological situation. It was critical only in England itself, which was covered in fog, which fact created difficult conditions for taxiing aircraft at the airport, as well as for takeoff. Good weather was predicted for the route. The crews were told that the temperature during the flight would be between 11 and 14 degrees Celsius.

Arrival over Warsaw was to take place between 1 and 2 pm, final landing around 4 o'clock in the afternoon

General Irzycki’s speech

After having passed on this information, the American commander of the bomber division stood up and introduced the commander of the Polish Air Forces to the assembled, who in turn presented the following speech:

“On behalf of the Polish Government and Polish Air Force, I have come to visit you on this, the day America is aiding Warsaw. This day, awaited by millions in Poland, is undoubtedly historic. Warsaw has been fighting for 48 days and is at the end of its tether. The aid you bring may be decisive in saving many human lives and be a contribution to the final victory. I am convinced that you will perform well. I wish you good luck with the task that awaits you.”

Thunderous applause greeted this speech. As the officers of the American Staff told us, all the crews were preparing to undertake this mission with great enthusiasm and with a great deal of heart. They were fully aware of the magnitude of their task and its uniqueness.

The commander of the operation was the last to speak:

“I'm not a historian,” he said. But we all know the name of Kościuszko, who was Polish and took part in the war to make America free. Today you have the opportunity to repay Poland for what he did for us at that time. I am convinced that we all are happy to take this opportunity.”

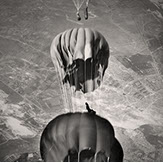

The briefing was over. The crews went to their preoperational breakfast and then to their aircraft. We ourselves went to see one of them and examine how the containers were loaded. In the middle of the Fortress's fuselage, where the bombs were normally loaded, were the containers. They were metal cylinders, about 180 cm long. To the upper part small, rolled-up parachutes were attached. 6 parachutes were in line in a bundle of silk cords, which were attached to a part of the skeleton of the aircraft, thus ensuring their opening after the container hung on them at the time of the drop.

Finally, the aircraft took off...

There sound of engines roared from all sides. The aircrafts were not visible, for although the sky was already brightening up, the fog was still over the ground. Our driver could hardly find the airport control tower, from which we were to observe the start of American squadrons. The glass room on the first floor of this turret, surrounded by a balcony, was at this moment the nerve center of the whole expedition. Every now and then, through the megaphone, the voices of the Flying Fortress captains could be heard, controlling the radios or stating the exact time and asking for final details before takeoff. The phones connected to the headquarters rang continuously, giving information as to what was happening at other airports, from which further squadrons were also expected to take off.

The commander of the bomber division sat at the main table and was put through to the staff in order to carefully coordinate the time of the bombers' departure with the departure of the fighters. And slowly the day dawned. On the balcony, the American commander of the operation was talking with our major K., asking for more information related to Warsaw. They also discuss the conditions of the container drop with the help of the parachutes. “Of course, this is not a bomb, so we cannot guarantee an equally accurate drop, where the parachute gives a specific direction and a specific rate of descent”, said an American colonel.

Finally the planes took off. As we know, the drops were successful. The fighter planes from the British bases returned without a loss, having made a huge landing flight. Warsaw during this operation received help, which exceeded the total number of all previous drops in the earlier operations.

Source: A description of the preparations for operation Frantic-7. Dziennik Polski and Dziennik Żołnierza (The Polish Daily and Soldiers Daily published in London), R.1, 23 September 1944, no. 223

B Artykuł: „Latające Fortece startują…”

The Political background of the Frantic 7 operation → PHOTOS +

The tragic finale to FRANTIC operations was the protracted effort, expended largely in appeals and negotiations, to deliver supplies to the besieged patriot force in Warsaw during August and September 1944. „This army, led by Gen. Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski, rose against the Nazis on 1 August 1944 upon receipt of what the Poles in Warsaw and London regarded as authentic radio orders from Moscow. The Soviet armies were approaching Warsaw and it seemed that the Polish capital might be delivered in a matter of days after Bór’s uprising. The Russian advance in that direction mysteriously halted, however, and came no closer to the city than ten kilometers for months thereafter. The rebellious Poles, facing powerful and vengeful German forces, fought on with typical bravery, and on 15 August General Eisenhower received a message from Washington urging him to undertake a supply-dropping mission to the beleaguered city. Heavy bombers were unable to complete an England-Warsaw-England fight, and it was very difficult to carry out a round-trip mission from Italy to Warsaw. Hence a shuttle to FRANTIC bases seemed in order.

But at this point the course of events took a dismaying turn. Russian officials suddenly denounced the Warsaw forces as reckless adventurers who had risen prematurely and without Soviet incitement and refused to permit a FRANTIC operation in behalf of Warsaw. Strong pressure from the American and British ambassadors failed to alter the Soviet attitude, as also di dan appeal from President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill. The British, employing the Italy-based RAF 205 Group with volunteer aircrews, between 14 August and 16 October sent seven exceedingly difficult and costly relief missions to drop supplies by night. But while the Germans were beating down the Poles and destroying Warsaw stone by stone, as they had said they would, the Russian army did not budge from its position ten kilometres away, and some high-ranking officers in USSTAF were of the opinion that further insistence on supply-dropping could only endanger Russo-American relations with no other effect.

By early September the situation had become so tragic, however, that the western Allies renewed their appeals for a FRANTIC mission to Warsaw. The Russians gave their approval on 11 September and, perhaps as a concession to the western Allies, they themselves commenced dropping supplies on the Polish capital on 13 September. The only American mission of this nature, and the last of all FRANTIC operations was carried out by the Eighth Air Force on 18 September. One hundred and seven B-17’s circled the area for an hour and dropped 1,284 containers with machine-gun parts, pistols, small-arms ammunition, hand grenades, incendiaries, explosives, food, and medical supplies. While at first it appeared that the mission had been a great success, and so it was hailed, it was later known that only 288, or possibly only 130, of the containers fell into Polish hands. The Germans got the others.

A strong disposition remained in Allied circles to send another day-light shuttle mission to Warsaw. The Polish premier-in-exile, Stanislaus Mikołajczyk, made a heart-rending appeal to Prime Minister Churchill, who telephoned USSTAF on 27 September to repeat endorse the Pole’s message and to add his own request for another supply mission, ”a noble deed,” as he called it. From Washington, President Roosevelt ordered that a FRANTIC delivery to Warsaw be carried out, much to the discomfiture of the War Department and its air Staff which regarded such missions as both costly and hopeless. The second supply operation was never cleared by the Russians; Stalin himself seems to have refused permission on 2 October 1944. A few days later the Nazis extinguished the Warsaw insurrection, which had cost the lives of perhaps 250,000 Poles. Not until January 1945 did the Russians take over the city, or what remained of it.

Source: Volume three, Europe: argument to v-e day, January 1944 to May 1945. The Army Air Forces in world war ii. Prepared under the editorship of Wesley Frank Craven – Princeton University, James Lea Cate – University of Chicago. New imprint by the Office of Air Force History Washington, D.C, 1983.

From the memoirs of Gen. Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski, Commander of the Home Army

“(…) This time, however, the popular song “One more Mazur today” ended the radio program. Immediately afterwards came a dispatch saying to expect a drop between eleven and noon.

It was a calm, sunny autumn day. A cloudless sky. The inhabitants of Warsaw, of course knew nothing about the help to arrive, and so the sight of approaching American planes, which appeared unexpectedly over the city, caused indescribable joy. The bombers were flying very high, leaving in their wake a series of white dots in the sky. Parachutes. The Germans opened with a thunder of fire from anti-aircraft artillery, which, however, did not reach the machines.

Warsaw experienced a moment of undiluted enthusiasm. Everyone, except for the sick and wounded, went out from the cellars. With the underground shelters now emptied, the courtyards and streets were thronged with people. At first it was assumed that airborne units were dropping in. A soldier standing near me was observing the sky through binoculars. Suddenly he shouted:

- God help them! The Germans will shoot them all!

One of the officers tried to calm him, explaining that they were no paratroopers, only containers with weapons and supplies.

- But I can see clearly through my binoculars their legs waving in the air – the soldier insisted.

The Germans seemed to have made the same mistake, alarming their troops with the warning: “Amerikanische Fallsschirmjäger”.

Shrapnel from the anti-aircraft artillery exploded again and again in the air, occasionally striking individual parachutes, the containers then plummeting straight to the ground.

The parachutes, which immediately after being dropping hung directly over our lines, were being caught by the wind and carried further and further away. Most of them and their load fell onto streets and houses that had still been in our hands a week earlier, but which were now held by the enemy.

When the planes flew off, the crowds which only a moment before had been gazing into the sky, cheering joyously, returned to the basements and shelters with sadly bowed heads. Our people understood how much help we would have had, had it arrived earlier. In the first weeks, when we were holding two-thirds of the city – about a thousand of the containers would undoubtedly have fallen into our hands. With such a large amount of weapons and ammunition, we would have been able not only to liberate all of Warsaw but also to hold it. Now, unfortunately, we held only swathes of the previously acquired area. Just a small portion of the containers dropped from such a great height landed inside our positions. We witnessed a great demonstration of Allied air power, but alas – it had come too late. (…)”

Source: The Memoirs of General Bor-Komorowski “The Secret Army”, Bellona Oficyna Wydawnicza Rytm, Warsaw 2009

REPORTS FROM WARSAW’S INSURGENTS CONCERNING THE AMERICAN DROPS → PHOTOS +

DISTRICT ONE

Kazimierz Brzuszkiewicz “Robert", “Robert Sobański", corporal officer cadet from Battalion “Golski”, southern area of central Warsaw

“(…) Do you remember the British and American drops?

Yes, of course, but that was at the end of the Uprising. After all, those poor guys and parachutes flew in, the sky was white, but ninety percent (of the drops) fell into the hands of the Germans. Chocolate, food, medicine, and weapons above all. If it had been a month earlier, the situation would have been different. (…)”.

Source: Spoken History Archive at the Warsaw Rising Museum

Rena Anna Syska-Lamparska Kwaśniewska a civilian from downtown Warsaw

“(…) Were these drops by the allies?

Our drops, allied ones. These drops were... There are no words to describe it. We know that our soldiers were in the RAF, our planes and these planes... England - as far as I know - did not send any aircraft. These were our airmen who flew to Warsaw with aid. There were drops - not all of them succeeded, because some of them fell on the German side, but from what I know (from Zagórski in turn) the whole list of arms drops that fell on our positions, into Polish positions, were a huge help. (…)”.

Source: Spoken History Archive at the Warsaw Rising Museum

DISTRICT ONE

Krzysztof Rowiński “Żbik”, communication link man “Krybar”, Powiśle district

“(…) In the middle of September there was one beautiful American drop, involving over a hundred Flying Fortresses, Mustangs were guarding them, the fighter planes. They arrived flying very high above Warsaw. Suddenly colorful parachutes appeared, people thought that it was the Independent Parachute Brigade, in which my father in fact belonged. The Germans even fled in some places. It turned out later that these were drops. Most of them fell into German hands, because then only the Śródmieście [the area of central Warsaw] was in our hands. There were very few areas where they could be successful [such drops]. So, the Germans ate well, as there were various tinned foods and, other things. So it helped the fighting Germans, [though] they didn’t need it, but they got extra [rations]. The drops were interesting. One large American drop was of course much bigger than all the British drops that had happened before. (…)”.

Source: Spoken History Archive at the Warsaw Rising Museum

DISTRICT ONE

Mieczysław Teisseyre “Teść”, corporal cadet, 104 Company of Syndicalists (a pre-war trade union group) in the Old Town

“(…) Do you remember any drops?

Yes, I remember, I remember well, [especially] the biggest drop there was. Literally the whole sky was then covered with parachutes. It was in the afternoon, as far as I remember. [The sky] full of parachutes, amazing joy, landing, the British and so on, the sound of these bombers, German artillery fire, exploding missiles and these containers landing, Unfortunately, it was a gigantic drop, only some of these containers reached the Old Town, but not many. At Krasiński Square we ran for these bins, we got some arms, there were launchers, anti-tank grenades, spring operated - a very interesting design, monstrous recoil, could break one’s shoulder if a careless person used it. Yes, that drop... then, I remember, it crashed, one bomber fell on the corner of Miodowa street. The wreck lay there for a long time, I don’t know if anyone was saved, I don’t remember. I do know that they dismantled machine guns from that bomber, I remember that well. (…)”.

Source: Spoken History Archive at the Warsaw Rising Museum

DISTRICT ONE

Daniela Piasecka “Biała”, marksman, paramedic, liaison person, group “Chrobry II” Śródmieście Północne (north-central Warsaw)

“(…) Do you remember the drops?

Of course. I was even on the drops. We even got an American drop. There was even halva and other delicacies, weapons, lots of good weapons. But also a lot went to the German side. I remember how the Russkies threw us dry crackers and Pepeszas on strings. When one fired them, it was possible to bend the barrel. It was such steel that when it warmed up it was no use at all. You aimed in one places and the bullet went elsewhere. Pepeszes on string. We also got drops like that. There were not many of them, but there were some. If they made it possible to start somewhere, in a field [...] They asked the Russkies to make them available. On the Praga side, they knew what was going on in Warsaw, the guys used to swim to the other side. Naturally, from the Old Town, where it was the shallowest and the narrowest. But the Russians took care of them (killed them), one two and all trace of them was lost. Unless they came across a Polish unit. Because there were also Polish units there [on the Russian side of Warsaw] (…)”.

Source: Spoken History Archive at the Warsaw Rising Museum

REPORTS OF US AIR FORCE SOLDIERS (PARTICIPANTS OF OPERATION FRANTIC-7) ON THE SITUATION IN WARSAW DURING THE UPRISING → PHOTOS +

(…) The Associated Press reports from Moscow what two American airmen have to say: Sergeant. T. Agrasso from Paulsboro, New Jersey and Sgt. J. Spreng from Cleveland, Ohio, participants in the expedition of Flying Fortresses to Warsaw.

Sgt. Agrasso said: “Warsaw looks like a city in which heavy battle is being waged. The whole city was engulfed in smoke.”

Sgt. Spreng said: “We never flew so low during any operation. Never have I seen such a fierce battle. All the buildings were either flattened or ruined. Thick smoke hung everywhere.”

Źródło: Dziennik Polski i Dziennik Żołnierza, nr. 223.R.1, 23 września 1944. [wydawany w Londynie]

B Artykuł

Prime Minister Mikolajczyk’s message to President Roosevelt of 19 September 1944 regarding aid to Warsaw → PAPER A

To the President:

Mr. President, please accept the heartfelt thanks which I have the honor of passing on to you on behalf of the people of Warsaw for the very effective help given to the defenders of the Polish capital by the marvelous American Air Force. We owe it to you, Mr. President, that this operation was successfully carried out, as you, the Commander-in-Chief of the US Military Forces, ordered it to help the Warsaw insurgents who for seven weeks have been fighting alone against the Germans. This extraordinary example of American interest in and active help for those fighting for freedom will remain deeply engraved in the hearts of all Poles. Uplifted by this tangible proof of our brotherhood of arms, the Poles in Warsaw and all over Poland strongly believe that in their struggle against the barbaric German enemy they will continue to receive, until the final victory, Allied assistance – and that their growing needs for supplies, especially food and medicines, will be fully met.

Mr. President, please express our gratitude to the commanders and courageous pilots who devotedly and with a sense of responsibility undertook this dangerous operation, as well as expressions of the Polish people’s warmest sympathy to the families of those who lost their lives in the brave attempt to provide the necessary help to their Polish comrades in arms.

/ - / Stanisław Mikołajczyk

“The Department of State Bulletin” / Vol XI. No. 275, page. 350, 1.X.4

Source: Piotr C. Śliwowski archives

Akt. IV s. 347 / Nr 1099 / 18.IX

DELEGATE OF THE GOVERNMENT TO THE PRIME MINISTER: ABOUT THE DAYTIME DROPS OF THE AMERICAN EXPEDITION → PAPER A

ENCODED DISPATCH / Lena (code name) / L. dz. K. No. / September 18, 1944 / Received and deciphered on 20.9.44 / Stem (code name)

Stem (code name)

Thank you for today's drops. I do not yet have any information about their content. Some of them fell into the hands of the Germans, some of them fell in Praga district (into the hands of ) the Soviets, but the very fact of help from the Allies had an extremely positive effect on the population and the army. People jumped for joy. However, it cannot be a one-off operation, it must be long term, then its real and political impact will be enormous, otherwise the Soviets will have a monopolistic position. The most needed articles are: food other than sugar, ammunition and medicines, without this we (our efforts) will collapse.

Source: Piotr C. Śliwowski archives

No. 1097

HEAD OF O.VI STAFF NW TO THE COMMANDER OF THE AK (Home Army) AND THE COMMANDER OF THE BASE IN BRINDISI: NOTIFICATION OF THE LAUNCH OF THE AMERICAN AIR OPERATION TO DELIVER AID TO WARSAW → PAPER A

CODED DISPATCH / O.VI L. dz. 8549 / XXX / 111 / Secret / September 18, 1944.

Avalanche [and] Elba

At dawn, over a hundred fortresses with escorts set off to you [Warsaw]. Expect approx. 12 MEZ. They will not bomb. The containers will be in the air for 7 minutes, hence great dispersion is possible. Provide initial results immediately. Wanda 311 tags are discontinued. They fulfilled the task. / Guard

Source: Piotr C. Śliwowski archives

Doc. IV page 350 / 18.IX.44 / No. 1103

COMMANDER OF AK (THE HOME ARMY) TO THE COMMANDER AND CHIEF OF THE POLISH ARMY: ASSESSMENT Of THE AMERICAN DROPS

No. 852 / VV / 111 / O. VI L. dz. 8662 / secret / 44 / Wanda 7 TO HEADQUATERS. / RECEIVED AT 19.52, on 19/9/44 / September 18, 44 / Sent at 19.20, dated 19/9/44, / DECIPHERED AT. 21.45 /CODED DISPATCH

At 6188 (686): 235 (map reference) About one hundred containers dropped in the Środmieście district, most with armaments. As yet there are no reports from the Mokotów, Żoliborz, and Czerniaków districts.

Operation flaws of drops:

1) high altitude - parachutes undergo several layers of different air currents.

2) Direct drops from the flight path without recognizing the drop signals, hence very limited drop precision.

3) The drops are carried out by very large aircraft which are difficult to maneuver, which means uneven coverage (of drops).

More information to follow

Lawina (code name) 1852

Source: Piotr C. Śliwowski archive

Dispatch code /No. 852 / VV / 111

From Wanda 7 to the Headquarters / on 19.9.44 → PAPER A

issued on 19.9.44 hours / Top secret /

Lawina (code name) to Warta (code name)

On 6188 (686) – map reference) in Śródmieście, about one hundred containers, most with armaments. There are still no reports from Mokotów, Żoliborz and Czerniakow.

Operation flaws of drops: 1) high altitude – parachutes undergo several layers of different air currents. 2) Direct drops from the flight path without recognizing the drop signals, hence very limited drop precision. 3) The drops are carried out by very large aircraft which are difficult to maneuver which means uneven coverage (of drops).

Further details to follow.

Lawina 1852. on-18.9.44Stamp of: THE INSTITUTE IN LONDON WHICH IS RESPONSIBLE FOR THE HISTORICAL DOCUMENTATION OF THE POLISH UNDERGROUND’S OPERATIONS.

Source: Piotr C. Śliwowski archives

Akt. IV s. 352-353 / Nr 1107 / 18.IX

Abstract from the report of the US Eight Air Force Command

The course of the flight over Warsaw → PAPER A

C o n f i d e n t i a l

Extract

2. Bomber Report

Three combat wings (110 B-17s) dispatched to drop supplies at Warsaw. Three a/c returned early. All formations dropped on Primary visually. Approximately 1284 containers dropped with fair to excellent results. 105 a/c landed at Russian bases. Flak: Moderate, accurate. E/A Opposition: Nil. Claims: Nil. Losses: 2 B-17s, cause unknown.

Source: Piotr C. Śliwowski archives

Nr 1117 / 20 IX

RESULTS OF THE AMERICAN FLIGHT DATED 18 SEPT. 1944 → PAPER A

O. VI to L. dz. 8662 / tjn / 44 / September 20, 1944

Results of American flights carrying equipment for Warsaw on September 18, 1944.

[Prepared. O. VI staff NW]

The following took off:

Fortresses, each with 12 containers – 110

Fighters in 2 groups – around 120

The following turned back en route: 3 fortresses

Take offs: 2 fortresses

2 fighters

Total: 4 planes

In total, about 1,250 containers were dropped over Warsaw (each containing around 100 kg net of equipment). In the following ratio:

About 200 containers in the Żoliborz district

Around 750 containers for the Śródmieście district

Around 300 containers for the Mokotów district

Total about 1,250 containers

According to the reports collected by September 20, 1944, the results of the drops were as follows:

1. Żoliborz: Failure/ missed drops, the containers landed in the area of Góry Szwedzkie on sites held by the npla (code) about 4 km west of the destination.

2. Śródmieście : The center of the drop northeast of the target. The containers were collected in the northern part of the area. Some of the containers, probably from this group, landed in the Wisła (river) and Praga district.

3. Mokotów: The center of the drop approx. 2 km to the east of the target, the containers dropped on the outskirts of their own fighting groups A night operation was planned for their recovery.

More detail is not available for the time being.

Up to now, the pickup of approx. 130 containers has been officially confirmed, i.e., over 10% of the total and over 17% dropped in the Śródmieście district.

It should be expected that the receipt of a large number of containers, especially those containing food, will never be officially confirmed, as they will be immediately consumed by the population. The same applies to equipment that has fallen on areas only weakly held by the enemy, where the weapons will probably be secured.

Further confirmation of receipt is to be expected, which will increase the number of containers already accounted for.

Source: Piotr C. Śliwowski archives

First operation, 18 Sept. 1944 (England to Russia) Eighth Air Force

A/C Dispatched: 110 B-17 and 150 P-51 (86 P-51 to return to England, 64 F-51 to continue to Russia).

A/C Attacking – 107 B-17 / Target – Warsaw / Tonnage – 1284 Supply / Results – 37% containers recovered by Polish forces.

E/A Opposition: None to bombers to bombers. Fighters had encounters with 8 E/A in Schleswig area.

Flak: Accurate and intense.

Claims: 4-0-0 (air) / 3-0-6 (ground) / Losses: 1 B-17 (1 B-17 landed Breast Litovsk) / 1 P-51 from penetration escort / 2 P-51 from withdrawal escort.

Major Battle Damage: 10 B-17 / Minor Battle Damage: 30 B-17, 3 P-51

Narrative: On 15 Sept. 1944, 110 B-17 and 156 P-51 were airborne on Frantic 7 but turned back to U.K. due to adverse weather. On 18 Sept. 1944 mission, 2 B-17 returned early to U.K.