POLSKI

GHETTO UPRISING IN WARSAW

The Ghetto Uprising in Warsaw of 19 April 1943 was the first and the largest single Jewish revolt of World War II. The uprising also marked the first time during the war when non-Jewish fighters fired shots to aid the Jews. Two flags, hoisted by the insurgents on the roof of a burning building visible on both sides of the Ghetto wall, became a symbol of defiance – and of the Jewish-Polish allegiance: the Zionist white and blue and the Polish white and red flew side by side.

THE ROAD TO THE REVOLT

The Ghetto is Created

There was no Ghetto before the war. When the Germans ordered the creation of the so-called Jewish Quarter shortly after their 1939 invasion of Poland, they instituted legal and physical apartheid. The German occupiers built an actual barrier to cut off Warsaw’s Jews from the city’s Christians: a thick, 10-foot tall wall with barbed wire atop it, running the entire length of the 10.5-mile Ghetto perimeter. Forming the Ghetto was accompanied by a forcible relocation of the city’s Jewish and Christian population. Christians and Jews alike were expelled from their homes to set up “purely Aryan” and “purely Jewish” areas of settlement. All unauthorized contact with the Jews, particularly any form of assistance, was punishable by death.

The victims of the expulsion on both sides of the wall naturally opposed this forced relocation, but neither had the power to stop it. According to Jewish scholar and Warsaw chronicler Chaim Kaplan:

“[A]ll the [Poles] living in the streets within the walls must move to the Aryan quarter. To a certain extent the edict has hurt the Poles more than the Jews, for the Poles are ordered to move not only from the ghetto, but from the German quarter as well. Nazism wants to separate everyone …The Gentiles too are in mourning. Not one tradesman or storekeeper wants to move to a strange section, even if it be to an Aryan section. It is hard for any man, whether Jewish or Aryan, to start making his life over. And so the panic in captured Warsaw, occupied by harsh masters, is great. … for the time being we are in an open ghetto; but will end by being in a real ghetto, within closed walls.”

Fully a third of the city, some 400,000 people, found themselves trapped in a walled-off area of about 1.3 square miles. For the Jews in particular, the congestion of the new places was unbearable. Moving elsewhere was not an option. Food was scarce and tightly rationed by the Germans on both sides of the newly erected barrier, but particularly so in the Ghetto. Overcrowding and collapse of basic services resulted in diseases, starvation, and death. The black market was a potential source of additional food, but it was illegal, and, as with most rules imposed by the Germans, punishable by death.

The Polish Underground Reacts

The Polish Underground State unequivocally condemned the creation of the Ghetto. This reaction merely reflected generally pro-Jewish attitude prevalent among the people of Warsaw since September 1939 as they reacted with sympathy to the vicious persecution of the city’s Jews.

The Underground’s clandestine Warsaw Information Bulletin of November 1940 was clear:

“The Warsaw ghetto takes on the dimensions of a gigantic crime: over four hundred thousand people are being condemned to all the consequences of unavoidable epidemics and a slow death from hunger.”1

Even the most extreme groups of Polish nationalists warned Poles against joining the occupying Germans in any anti-Jewish measures. Any such collaboration, according to the Underground code of conduct, was punishable by death and treated like treason.

German and Jewish scholarly sources confirm the reactions of the Polish Underground and the sentiment of the Polish people towards the Jews, regardless of their peacetime political leanings and attitudes. For example, German army general Johannes von Blaskowitz noted on February 6, 1940:

“The acts of violence carried out in public against Jews are arousing in the Polish population, which is fundamentally God-fearing, not only the deepest disgust but also a great sense of pity for the Jewish population.”2

Jewish scholar Chaim Kaplan wrote down in an entry for 5 December 1939:

“We thought that the ‘Jewish badge’ would provide the local population with a source of mockery and ridicule—but we were wrong. There is no attitude of disrespect or of making much of another’s dishonor. Just the opposite. They show that they commiserate with us in our humiliation. They sit silent in the streetcars, and in private conversation they even express words of condolence and encouragement. ‘Better times will come!”

Even Rabbi Silverstein (Zilbershteyn) of Warsaw who felt that the Poles were indifferent toward the Jews noted that “in many cases they also expressed their sympathy. There was not a single instance when they exhibited a hostile attitude.”

Chaim Kaplan observes a lack of susceptibility to German anti-Semitic propaganda among the Poles. He wrote in a 1 February 1940 Warsaw Diary entry:

“[T]he oppressed and degraded Polish public, immersed in deepest depression under the influence of the national catastrophe, has not been particularly sensitive to this [German anti-Semitic] propaganda…Common suffering has drawn all hearts closer, and the barbaric persecutions of the Jews have even aroused feelings of sympathy toward them. Tacitly, wordlessly, the two former rivals sense that they are brothers in misfortune; that they have a common enemy who wishes to bring destruction upon both at the same time.”

The Ghetto is Walled Off

From the outset, the Warsaw ghetto became a self-contained universe. Yet, the Jews devised ways to breach the wall. Some Poles helped by infiltrating in, but more frequently by helping Jews from the outside.

The Poles used to throw food, medicines and documents into the Ghetto for Jews preparing to escape. Individuals and sometimes entire families were successfully led out of the Ghetto by members of Polish underground organization “Żegota,” the Council to Aid Jews at the Delegate of Government of the Republic of Poland in Exile. After the initial rescue, “Żegota” would find shelter and provide new identities, including forged identity cards, food stamps, baptismal certificates, and money. The organizational needs of rescue operations that lasted throughout the years of German occupation, involved courage and good will of thousands of volunteers, willing to help strangers under the pain of death. Irena Sendler, a Polish nurse and a member of “Żegota”, helped smuggle out of the Ghetto and rescue some 2,500 Jewish children, later hidden in Polish homes or convents on the so-called Aryan side (non-Jewish side). Many of the children survived the war. Another member of “Żegota”, Władysław Bartoszewski, moved between the two sides of the Ghetto delivering help.

A lot of Polish citizens helped Jews, many of them paid for this with their lives and with the lives of their nearest and dearest. Germans imposed and strictly enforced the death penalty for anyone who helped Jews in occupied Poland, and Warsaw was no exception. On March 24th, 1944, for helping Jews the Germans murdered, in the village of Markowa near Łańcut, Józef and Wiktoria Ulma (who was near the end of her pregnancy) and their children, the oldest of whom was eight years old, and the youngest - one and a half years old. The eight Jews who they were hidden were also killed, among them two women and a child. Repression also fell on the inhabitants of the area.

Nevertheless, rescue efforts continued throughout the war. The sheer size of the Ghetto’s population – 400,000 men, women, and children, or a third of the city’s inhabitants – made any attempts to aid the Jews extremely difficult. Helping the unassimilated who did not communicate well in Polish was harder still. And yet, “Żegota” was created for no other reason but to aid Jews, the only such organization in all of occupied Europe. Seeing the extermination of Poland’s Jews and no response to the Polish Underground State’s appeal to the allies for help, the group’s founder, writer and devout Catholic Zofia Kossak Szczucka, wrote her Protest distributed clandestinely as a leaflet throughout Warsaw on August 11, 1942:

“The world is looking at this crime, more terrible than anything that has been seen before – and is silent. The slaughter of millions of people continues in ominous silence.”

And the Ghetto desperately needed the world to notice. From the moment it was created, the Ghetto could not have survived without outside help – Polish aid to Jewish food smugglers and black marketeers was indispensable. According to Jewish witness and historian Emmanuel Ringelblum:

“This was a widespread phenomenon…..Hundreds of beggars, including women and children, smuggled themselves out of the Ghetto to beg on the Other Side, where they were well received, well fed, and often given food to take back to the Ghetto. Although universally recognized as Jews from the Ghetto, perhaps they were given alms for that very reason.” 3

An Italian journalist visiting Warsaw at the time, similarly observed:

“Through the openings very carefully made in the walls of the ghetto teams of starving Jewish children made their way to other districts of the city to look for bread. With fear in their eyes, these poor, dark-haired youths banged delicately on the doors of Polish homes and always met with understanding: they were given bowls of soup and pieces of bread. Then sneaking along the walls in order not to be caught, they ran to the opening in the wall and blended in with the mass of Jews.” 4

The vast majority of Ghetto Jews barely had enough to survive. The poor starved and died en masse of diseases and hunger. The affluent few lived, for now, along with the Die Prominente, or the Jewish Council (Judenrat) and the Jewish Police, who collaborated with the German occupiers in hopes – in the end, futile – of saving their own lives. With some exceptions, desensitized by the Germans cruelty and their own fear, they gradually became a blind instrument for exploitation and oppression of their own people. The Jewish Ghetto Police either deserted and hid – or joined the ranks of collaborators. They formed the most numerous force that – under the pain of death – was forced to round up and help deport the Warsaw Jews to their deaths in the summer of 1942.

Faced with a similarly impossible choice but unwilling to partake in the destruction of his own people, the head of the Jewish Council, Adam Czerniaków, committed suicide rather than help the Germans send men, women, and children to the gas chambers.

The Ghetto Underground in Warsaw and Armed Resistance

Paradoxically, at least until January 1942, the German civilian authorities considered the Ghetto in Warsaw a politically compliant area. It was far from the truth. Jewish political resistance was born as the Polish State collapsed at the beginning of World War II. Most pre-war political parties and groups remained, shifting their activities underground. Even the Orthodox circles focused on clandestine education. Others plotted. For example, General Zionists (Gordonia) and religious Zionists (Mizrachi) continued to assemble and analyze the situation via the prism of their respectively centrist and center-right points of view. They supported the western Allies, and were skeptical of, if not outright hostile to, the Communists and the political left in general. Some of the Jewish leaders, in particular on the left, fled to Soviet-occupied Poland. The rest reconstituted secret skeletal organizations in the Ghetto in Warsaw and elsewhere under German occupation. Some argued for armed resistance.

The hard nationalist Zionists-Revisionists established their own clandestine National Military Union/Jewish Military Union (Irgun Zvai Leumi/Żydowski Związek Wojskowy – ŻZW), led by David Apfelbaum and Paweł Frenkel. The Irgun, a conservative paramilitary Jewish organization active in pre-war Poland and later critical in the creation of the Jewish State in The Holy Land, prepared itself for armed struggle from the very beginning. When asked about the secret store of weapons and German uniforms that the Irgun carefully and deliberately accumulated in the Ghetto, Irgun/ŻZW leader Dawid Wdowiński explained:

“The command of Irgun Zvai Leumi [Jewish Military Union] was in contact with the Polish underground movement. For a short time they sent us military instructors to teach our people. Our fighters had to learn how to handle various weapons and hand grenades. Besides this they learned how to build barricades, how to behave in street battles, how to defend the bunkers. The contact with the Polish military organization made it possible for us in the beginning to buy weapons, hand grenades, Molotov cocktails, munitions. Later, we had our own sources of supply. Besides, one could always obtain these things in limited quantity from German soldiers who for money and gold would do anything.”

While the Irgun/ŻZW was a disciplined and well-trained military group, its ideological rivals on the left formed something akin to revolutionary militias in the Ghetto. The much more numerous parties on the political left, including Marxist and social democratic Bund, leftist Zionists, and the Communists, who resurfaced as the Polish Workers Party (PPR), eventually founded the Jewish Fighting Organization (ŻOB). Mordechai Anielewicz of the Poale Zion led the group, and Bundist Marek Edelman served as his deputy.

The small Communist underground in the Ghetto grew over time, strengthened by the Soviet victories on the Eastern Front. They remained under direct supervision of Stalin’s secret police, the NKVD, as did the Communist underground outside the Ghetto walls.

On orders from Moscow, the Communists schemed to take over the Jewish Fighting Organization under the guise of a “united front” but failed, mostly because of the Bund’s resistance to the Communists’ dominant role. Still, their position remained strong, largely because of the realization that Stalin would arrive in Warsaw before the Western Allies and the perception that the Red Army was more successful in defeating the Germans than anyone else.

Many ŻOB (Jewish Fighting Organization) members viewed the war as a clash of English and German “capitalists” and “imperialists,” and most Zionists considered Great Britain an enemy because of the kingdom’s control over Palestine. Some in the Ghetto dreamed that Stalin would establish a “Soviet Palestine” for them. Their clandestine the Ghetto in Warsaw press printed outright revolutionary and Soviet propaganda. Some underground publications went so far as to claim that “the Soviet-German Pact of August 1939 [that partitioned Poland] was a wise and justified move” because it bought Stalin time “to prepare in all ways to fight against this whole capitalist world, which is weakened by the war and its consequences.”5 The idea of “the victory of the Red Army and free Poland as a part of the Soviet Union” may have been appealing to the more radical elements in ŻOB but could hardly have been less popular with the Irgun’s ŻZW – or with the Poles on the other side of the Ghetto wall6.

Polish and Jewish Underground Interlinked

As the clandestine life in the Ghetto continued, some Jewish groups reestablished links with the Christian side of Warsaw, usually along pre-war political lines. And so, right-leaning groups in the Ghetto trusted the right-leaning groups on the outside, and the socialists cooperated with their equivalents. Added to that, the Polish Underground State and its clandestine Home Army that reported to the country’s Government-in-Exile endeavored to include all the political forces that supported free, post-war Poland. For that reason, the Polish Underground considered the Communists on both sides of the Ghetto wall to be beyond the political pale.

The Home Army counterintelligence was well aware of the Stalinist propaganda and the Soviet secret police infiltration of the left wing Jewish organizations in the Ghetto. Revelations of pro-Soviet sentiments in the Ghetto severely undermined many Poles’ sympathy toward the Jewish people and exacerbated the distrust some felt towards them after the Soviet invasion of eastern Poland (1939-1941).7

Despite distrust, the Home Army continued arming and training the Jewish underground. As ŻOB leader Marek Edelman explained:

“We didn’t get adequate help from the Poles, but without their help we couldn’t have started the uprising. … You have to remember that the Poles themselves were short of arms. The guilty party is Nazism, fascism—not the Poles.”

Armed Resistance Wasn’t the First Option

Before the idea of armed resistance triumphed, passive, non-violent resistance and accommodation were the rule - pretending to obey the German rules or discharging no more than the bare minimum of occupier-mandated demands necessary to avoid vicious repression. Such resistance meant opposing the German occupation order, including through clandestine education, secret community organizing, black market activities, and information dissemination.

Few collaborated since collaboration meant aiding the Germans to the detriment of the bulk of Jewish society. But even among Die Prominente, who did collaborate, there were those who endeavored to help their people and shield them from the increasingly onerous, bestial, and, ultimately, genocidal German orders.

Just who resisted, accommodated, or collaborated and how, after the sealing off of the Ghetto in Warsaw, remained in the state of constant flux. As the German terror increased, resistance weakened. But when it became clear that nothing, not even collaboration, guaranteed survival, and that non-violent resistance was inadequate, the rationale for armed resistance became clear. Understandably, no normal human being was ready to believe that the German occupiers actually meant to exterminate all the Jews, which is why most who cautioned against armed action did so out of fear of anti-Jewish reprisals by the SS.

However, the full understanding of the German plan did eventually set in – when the Germans deported most of the surviving inhabitants of the Ghetto in Warsaw, about a quarter million people, and murdered them in Treblinka in July 1942. Only then did all the remaining Warsaw Jews, not just the eager young fighters, see the horrific reality of the Holocaust. They resolved to fight against their executioners, knowing that they have no chance to prevail, and in the end realizing that they are fighting not for their lives but for a more dignified death.

THE REVOLT BREAKS OUT

The strategic objective of the April 1943 military uprising in the Ghetto in Warsaw was armed resistance to the Germans before the inevitable extermination of the remnant of the Jewish inhabitants; the insurgents aimed to kill as many Germans and their collaborators as possible before either perishing, sword in hand, or trying to flee to the non - Jewish side. As Yitzakh Zuckerman, one of the leaders of the revolt, put it, “For us it was a question of organizing a defense, not an uprising. In an uprising, the initiative is with the one rising up. We, we sought only to defend ourselves; the initiative was entirely on the side of the Germans.”

The Jewish fighters’ baptism of fire occurred three month earlier, on 18 January 1943, when the Germans and their helpers attempted to round up the remaining Jews in the ghetto. The SS were then met by roving squads of the Jewish Fighting Organization (ŻOB), spitting bullets and throwing gasoline bottles and grenades at them. The occupier withdrew in confusion. There was an eerie respite, while both sides regrouped.

On 19 April 1943, acting on the orders of the SS and Police Reichsfuehrer Heinrich Himmler himself, under the personal command of SS-Brigadefuehrer Juergen Stroop, 2,500 men of the SS and the Wehrmacht, deployed, along with regular infantry weapons, heavy machine guns, artillery, and armor. They were assisted by foreign SS volunteers: Latvians, Lithuanians, and Ukrainians.

Opposing them, poorly armed Jewish forces consisted of the Jewish Fighting Organization, the Irgun (ŻZW), and various unaffiliated volunteers. The ŻOB fielded up to 500 men, Irgun (ŻZW) half as many though their fighters have been professionally trained. As many as 100 participants operated in “wild groups.” They were mostly armed with gasoline bottles and small arms, a few submachine guns and a score of rifles – and they were determined to fight till the end.

The weapons came from the Polish underground on the outside. During the fighting, a group of Jewish insurgents aligned with the Irgun Zionists symbolically flew two flags side by side on the roof a building visible from the other side of Warsaw.

Irgun and ŻOB had been collaborating for some time, but their cooperation was chiefly limited to swapping intelligence and agreeing to covering separate battle sectors. The rivals manned their respective barricades and strongholds, while the civilian Jewish population disappeared into bunkers under tenements and houses.

Fighting

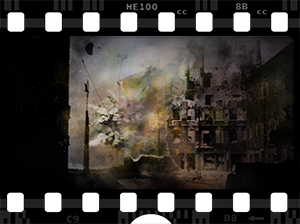

The fighting progressed through two distinct stages: street clashes and bunker defense. For about a week the Germans and their auxiliaries faced a series of street ambushes and engaged in running skirmishes with the Jewish fighters. A major firefight took place on the Muranowski Square, which was defended by the Irgun. They held out for about a day against overwhelming German force. They marked their territory and their allegiance by hoisting two flags, the Polish and the Zionist, on the roof of a burning building visible on both sides of the Ghetto wall.

Alicja Kaczyńska, who lived right outside the Ghetto, remembers the sight:

"On the roof opposite we could see people coming and going, and we could see that each of them was armed with some kind of weapon. At one moment we witnessed an exceptional sight on that roof – a blue-and-white flag and a red-and-white flag were raised. We all cheered. Look! Look! The Jewish flag! The Jews have taken Muranowska Square! Our voices echoed on the stairs. We hugged each other, hugged and kissed."

In the end, Most of the Irgun soldiers were killed. A few managed to escape.8

According to David Landau of the Jewish Military Union:

“The open fights came to an end with the battle that took place at Muranowska on 25 or 26 April…. By the time the battle was over on that spring evening we had lost a considerable number of our members. Many others were wounded... After that, our commanders informed us that arrangements were being made on our side and on the Aryan side to evacuate our group through the sewers to join the Polish partisan units in the forests. We were told that each of us was now free to decide to go with the group that was leaving, or to remain. From that moment on, everyone was free to make his own arrangements for the future…. We were told that we would not engage the Germans in any battle unless it became impossible to avoid it.”

The ŻZW fighters obtained detailed plans of the sewers from the Polish underground members, who also later guided them to safety9.

After the bloodied remnant of the Irgun disappeared into the sewers, the leftist ŻOB, which had hitherto essentially played a second fiddle, felt the full fury of the German assault. The Jewish Fighting Organization dispersed its militants and stubbornly defended its hiding places and bunkers. The Germans had to take them one by one in fierce struggle. Eventually, some of the ŻOB survivors escaped into the sewers and then, with outside Communist assistance, into the countryside.10

Those who remained behind fought to the bitter end. Almost all of them were killed or committed suicide, including the top commander Anielewicz. Oftentimes, bunkers were being located by Jewish informers, usually forced to reveal their position on the pain of death. At times, to avoid German losses, the Germans sent down Jewish policemen to ferret out the defenders and civilians hiding in the bunkers. Even though the Germans proclaimed the ghetto Judenrein on May 16th, mop up operations continued for a few weeks.11

Polish Underground Assistance

In addition to providing weapons, which were extremely scarce, maps, training, guidance, and logistics for the struggle and retreat, the Polish underground also supported the Jewish fighters militarily.

Polish help during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising marked the only time in occupied Europe when shots were actually fired to defend Jews during the Holocaust.

There were two kinds of armed actions: sapper operations against the wall and hit and run assaults. The actions were ordered by the Home Army high command, in particular Colonel Antoni Chruściel (“Monter”).

Already on 19 April 1943, three Home Army sapper squads under Captain Józef Pszenny (“Chwacki”) set out to plant mines to blow up a section of the ghetto wall. The Germans spotted them, killing two lead men and wounding four more. The attempt failed, but several Nazi policemen died in the firefight.

On April 22, a Home Army unit engaged an SS auxiliary Lithuanian police patrol and wiped it out outside the ghetto wall.

On April 23, Major Jerzy Lewiński (“Chuchro”), Lieutenant Jerzy Skupieński (“Jotes”), and their sapper unit targeted the Pawia Street gate to the ghetto for destruction. The Germans counterattacked, forcing their retreat. While escaping, the Poles managed to kill 4 SS and policemen and damage their car.

In several instances, German guards of the SS and police were mowed down by the AK by the ghetto walls on Leszno, Orla, and Zakroczymska Streets as well as near the neighboring Powązki cemetery. During one such actions, Leszek Raabe (“Marek”) of the Socialist Fighting Organization engaged the Germans outside the Jewish cemetery, while his deputy organized the escape of the Jewish members of the Polish Socialist Party (PPS) from the ghetto.

In the most daring operation, a Home Army detachment of Captain Henryk Iwański (“Bystry”) infiltrated into the Ghetto in Warsaw and fought arm in arm with the Irgun. Iwański had cooperated with the Irgun since 1939 and now joined them in battle in 1943. Having sustained heavy losses, the Polish and Jewish units retreated from the Ghetto together through the sewers.

“We delivered (...) from 1940 to 1943 weapons, ammunition and grenades (...) In March and April 1943, before the outbreak of the uprising, we delivered large quantities of machine and handguns to the Ghetto, ammunition, a dozen or so boxes of hand grenades (...) During the uprising in the Ghetto our people, mainly firefighters - members of OW KB about 20 times provided the Jewish fighters with ammunition” – Henryk Iwański (“Bystry”) wrote.

The commanding SS general Jürgen Stroop in charge of liquidating the Ghetto, complained about the role of the Poles as his troops were “constantly under fire from outside of the ghetto, i.e. from the Aryan side.” The top German was particularly enraged by the Zionist Irgun and the Polish Home Army fighting together:

“The main Jewish group, with some Polish bandits mixed in, retreated to the so-called Muranowski Square already in the course of the first or the second day of fighting. It was reinforced there by several more Polish bandits.” 12

Stroop’s account was confirmed by a Polish underground newssheet, The Warsaw Voice:

“There were Poles in the ghetto, fighting shoulder to shoulder with the Jews in the streets of the ghetto against the Germans.”13

The punishment for helping Jews was death. According to Stroop’s report of April 22, the Germans captured “35 Poles” and shot them in reprisal. “At their execution the bandits collapsed shouting ‘Long Live Poland!’” In a similar document, a Dutch SS-man Franz van Lent states matter-of-factly, “Six Poles of the Polish Underground movement who had tried to help Jews were arrested and shot.”14

The Polish underground remained in regular contact with a Jewish liaison on the non – Jewish side and conveyed all his messages from the fighting ghetto to the Polish Government-in-Exile in London via a clandestine radio station. The Polish authorities informed the Allies of the uprising provoked by mass deportations and extermination of Warsaw Jews, asking for help. None was forthcoming.

Earlier Polish reports about the Final Solution were similarly ignored in Washington and London: those prepared between September 1940 and April 1943 by Witold Pilecki, who volunteered to Auschwitz and sent detailed information about the camp’s horrors from within; and an eye-witness testimony by Jan Karski, whose account of the war in occupied Poland failed to convince the US President or the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

Polish Civilians React to the Ghetto Uprising

The people of Warsaw, by and large, looked at the Ghetto Uprising and the desperate courage of the insurgents with admiration and compassion. The Germans, for their part, repeated their threats of death to anyone who would dare to help a Jew. Jews in hiding on the non -Jewish side of the city, observed the reactions of the Poles to the events in the Ghetto. They remarked on the respect the Poles expressed for the Jewish fighters’ courage, the solemnity with which that event was viewed, and the extent to which outside the Ghetto, the unexpected uprising crowded out all other conversations, among friends and strangers alike:

- Ludwik Landau, a renowned Jewish economist, wrote the following entries in his wartime chronicle:

“April 20, 1943: There was enormous commotion in the entire city … the dominant mood is one of compassion and approbation.

April 21, 1943: … even among those who are indifferent or hostile, there is a definite air of approbation, and everywhere there is an animated and even attentive interest.

April 22, 1943: The attitude toward the Jews of various groups in society seems to have changed favorably during the course of the fighting: in the direction of showing approbation for putting up resistance, and perhaps even a wider extent of compassion that has made itself felt.

April 26, 1943: New announcements were posted today … the chief of police of the Warsaw District not only reminded about the threat of death for providing any help to Jews outside the ghetto, but also warned that those who did not inform police about Jews outside the ghetto would be sent to penal camps.

April 30, 1943: This battle was greeted everywhere with approbation, it awoke compassion even among those who hitherto were rather unlikely to show it toward Jews, especially in light of the unequivocal attitude of the entire secret press.”

- Zdzisław Przygoda, a Pole of Jewish origin who was living as a Christian in German-occupied Warsaw, noted that the sympathy for the fighters was overwhelming:

“The Warsaw suburb of Żoliborz was inhabited by the middle class, largely members of the Polish intelligentsia. Many Jews were hidden among them.”

- Jacob Celemenski, a member of the Jewish underground on the non -Jewish side, observed with satisfaction the German unwillingness to risk confronting the insurgents and the openness with which the city expressed its admiration for the Ghetto fighters and their courage:

“I jumped on the first tram for Żoliborz [a district of Warsaw] so I could reach my contact before the curfew at 9 o’clock. Afraid to enter the ghetto, the Nazis were shelling it with artillery from afar.”

“The tram was buzzing with many favorable comments about the Jews …”

- Ruth Altbeker Cyprys, a Jewish woman who was hiding as a Christian on the Aryan side adds her observations:

“I would pass in tram alongside the ghetto wall several times a day …”

“My fellow passengers reacted variously to the sounds of battle in the ghetto. ‘Why should the Jews defend themselves?’, asked a woman in a hat with a pink feather. ‘You are wrong, the Jews are right,’ I heard an elderly man speaking gravely and saw him making the sign of the cross. ‘Serves them right, those vile German cowards. I heard yesterday the Jews killed ten German scoundrels’, interjected a workman. The tram was leaving the ghetto walls behind…”

- Alexander Donat, a survivor from the Ghetto in Warsaw recounted the Polish perspective: admiration and resignation. Poles knew they were next in line to die:

“After the January [1943] resistance … we occasionally heard Poles say things like, ‘Bravo...! That’s the way. Stand right up to them!’ Or, ‘They’re eating you for lunch and saving us for dinner!’ Or, ‘As soon as those sons-of-bitches have finished you off, it’ll be our turn.”

- Israel (Srul) Cymlich, overheard stories of the uprising when he was hidden in the Falenica suburb of Warsaw. What began as simple accounts of actual events taking place in the Ghetto exchanged between information-hungry Poles, evolved into comforting heroic legends:

“The Poles who came into the shop during the day told different versions of events, such as that the Jews had allegedly freed prisoners from the Pawiak prison [notorious German detention center in Warsaw]; that three aircraft had been shot down over the ghetto; and that ‘pitched defensive battles are being fought.’ But I didn’t put much faith in those stories. …”

“The heroic surge of the Warsaw ghetto became the most talked about topic.”

- Helena Elbaum Dorembus, a Jewish woman sheltered by Polish Christians in Warsaw remembers:

“Two neighbours, Boczek and Mrs. Zaleski, return from town with incredible reports. They tell of hundreds of dead Germans, wrecked tanks and wounded, frightened soldiers being taken to hospitals. Mrs. Zaleski seems to gloat as she praises the Jews for their heroism.”

- Hania Ajzner, a Jewish girl hidden among Christian residents of a Catholic boarding school run by the Sisters of the Resurrection, recalled seeing the Ghetto on fire and hearing the compassion and reverence with which her rescuers watched it:

“One night, Sister Wawrzyna came into the dormitory after the girls had already settled down. ‘Get up, girls, come up to the windows,’ and she drew aside the clack-out curtains. They could all see a red glow over the fields to the South. ‘That is the Ghetto, burning,’ she said. ‘There was an uprising in the Ghetto. You must all pray, girls, for there are heroes fighting and dying there.’

“Ania [Ajzner] stood there in silence. … It was a long time before they went back to their beds. It was the 19th April 1943.”

- Yitzhak Zuckerman, one of the leaders of the Jewish underground who was on the non - Jewish side when the revolt broke out observes the transformation of the city of Warsaw as its people watch the most downtrodden rise up and assert their dignity:

“We can say that the Polish street in those days was pro-Jewish. I’m not talking about fringe groups, who were thrilled that the Zhids were burned in the ghetto. …what was happening in the ghetto roused extraordinary respect for the Jewish fighters. The Polish [underground] press was full of excitement and wonder, not just some leftist and liberal leaders, but the simple sympathy of the masses. You had to be a real bastard to enjoy what was happening to the Jews at that time. …the general sympathetic atmosphere in the streets did help us a little; I felt it especially because I didn’t have documents and, all that time, I walked around, usually near the ghetto walls or at the manhole covers, along with a few people I had with me. …”

“As the ghetto was burning, I would mix with the crowd assembled to watch the ghetto walls. At that time, there was a lot of sympathy and admiration for the Jews, because everyone understood that the struggle was against the Germans. They admired the Jews’ courage and strength. But there were also some, mostly underworld characters, who looked upon us as bugs jumping out of burning houses. But you shouldn’t generalize from that. With my own eyes, I saw Poles crying, just standing and crying...”

The Warsaw Ghetto Is No More

On May 16, 1943, Jürgen Stroop, German SS and Police leader in the Ghetto in Warsaw in charge of putting down the uprising wrote in his Report: “The former Jewish quarter of Warsaw is no longer in existence. The large-scale action was terminated at 20:15 by blowing up the Warsaw Synagogue.”

Years later in prison, awaiting sentencing and later execution for crimes against humanity, Stroop recalled the matter of the two flags – Polish and Zionist – over the fighting Ghetto:

“[It] was of great political and moral importance. It reminded hundreds of thousands of the Polish cause, it excited them and united the population of the General-Government, but especially Jews and Poles. Flags and national colors are a means of combat exactly as a rapid-fire weapon, like thousands of such weapons. We all knew that - Heinrich Himmler, Krueger, and Hahn [Obersturmbannfuehrer Ludwig Hahn, commander of the Security Police in Warsaw]. The Reichsfuehrer [Himmler] bellowed into the phone: 'Stroop, you must at all costs bring down those two flags.”

The two flags came down, but a year later, in August 1944, the surviving Jewish fighters stood side by side with the Home Army soldiers and stood up to the German occupiers once again, for 63 days, in the Warsaw Uprising.

SEE PHOTOGRAPHS

SEE PHOTOGRAPHS

SEE PHOTOGRAPHS

SEE PHOTOGRAPHS

SEE PHOTOGRAPHS

SEE PHOTOGRAPHS

SEE PHOTOGRAPHS

SEE PHOTOGRAPHS

SEE PHOTOGRAPHS

SEE PHOTOGRAPHS

SEE PHOTOGRAPHS

SEE PHOTOGRAPHS

SEE PHOTOGRAPHS

SEE PHOTOGRAPHS

SEE PHOTOGRAPHS

SEE PHOTOGRAPHS

SEE PHOTOGRAPHS

SEE PHOTOGRAPHS

SEE PHOTOGRAPHS

SEE PHOTOGRAPHS

SEE PHOTOGRAPHS

SEE PHOTOGRAPHS

SEE PHOTOGRAPHS

ZOBACZ GALERIĘ